AI vs. Predators

An area of innovative, critical conservation tech where Aotearoa is leading the world is in control of invasive species; specifically, invasive predator control.

We’re talking rats, mice, possums, weasels, hedgehogs, ferrets, and perhaps the king of them all, the very clever stoat.

This work is obviously critical because Aotearoa’s native birds, reptiles, insects, and plants have had no defences against invasive mammalian predators that were introduced by Māori and European settlers. And their introduction was so sudden, the native species had little or no time to adapt. So they are dying out, rapidly, and New Zealand is in the midst of a biodiversity crisis.

According to reports from the Department of Conservation:

4,000 of NZ native species are classified as in “some trouble”

1,000 are classified as in “serious trouble” or facing extinction

More than 50 bird species have already become extinct

Four out of every five birds are in deep trouble – with some on the brink of

extinctionEach year over 25 million native birds are killed by non-native predators

Efforts at controlling these predators have utilised traditional methods like bait traps and poisons. But it’s simply not good enough. There aren’t enough hours in the day for the manual labour required in setting and baiting traps, monitoring them, then endlessly rebaiting them – especially in hard-to-reach rural areas or offshore islands. And the predators never stop – they eat and breed at an alarming rate. Plus, climate change (surprise!) isn’t helping. All the trapping and baiting in the world has barely slowed the rapid decline of native birds, plants, lizards, and bats. It’s a losing game.

To level the playing field, Aotearoa New Zealand scientists like Dr Helen Blackie have been developing more advanced tech tools over the past decade. Innovations like long-life lures, remote communications systems and, especially, artificial intelligence (AI) have come to the fore. Organisations like Predator Free 2050 Limited, the Department of Conservation (DOC), and others have supported this work.

Dr Blackie has been the Principal Biosecurity Consultant at Boffa Miskell Ltd. for the past seven years and was Associate Director at Lincoln University’s Centre for Wildlife Management and Conservation from 2010-2014.

MOTAT recently interviewed Dr Blackie about her work in the field, some tech solutions, and whether predator free Aotearoa is really possible.

MEET STOATS’ PUBLIC ENEMY #1

How do you respond when people say the existing tools to deal with predators are fine?

I would definitely say the existing tools are not fine. We've been using the existing tools for a long time now, and all we've managed to do is hold the current biodiversity crisis at bay. I work with a lot of big-scale projects, thousands of hectares, with hundreds of traps out and bait stations, and they're, like, "It's still not working."

The money involved in servicing and dealing with that traditional kind of single set trap and bait station is so high. The work we’re doing is all about making things more cost-effective, and more long-life, a "set and forget" technology. And you only need to send your staff out

there occasionally and you don't go back for another year. The tech is doing all the work for you.

The predators are relentless, they're 24/7 and you could never keep up with that.

And they breed so fast. Rats are the biggest problem, exponentially. Possums are a bit more manageable; we could eradicate possums now across the country if we wanted to – we've got the technology to do that. Stoats are going to be our biggest challenge to get rid of. Stoats are very smart and have an amazing ability to learn. We used to have them in big outdoor enclosures at Lincoln University to study their behaviour. They are vicious little things, but wow, they learn very fast. And stoats actually farm their own food. Rats, possums, and ferrets are nowhere near the same level of intelligence that stoats have.

What's some advanced tech that's around the corner that you're excited about?

The AI space – reliable AI. Our newest tools will be AI-driven traps; you leave a trap out for a long period of time, and it will only track a particular species that you choose. The problem we've got now is with some of the clever species in New Zealand, like Kia, they love to investigate and to tear apart everything. So they're not great in terms of bait being out in the environment, they have a go at that, too. We need control tools that can be put out for long periods of time that will only trigger on the pest species but are totally safe for all our non-targets.

AI real-time surveillance is the other big thing in terms of having devices in the environment. They think for themselves. If they see a stoat, they're able to tell you in real-time, at this location, they've just detected a stoat. You basically sit at home with a map on your screen, and it'll show you what's been detected, and where. On the flip side of that, we can use that tech for biodiversity as well, it doesn't matter what species is you're interested in. That real-time monitoring is going to be a big game changer.

AI has been a huge driver. About six of my current projects use advanced AI. When we started some of those, in 2010, it was really pushing the limits back then. And when I look at what we're able to do with it 11 years later, it's come a long way.

How would you describe AI?

It's basically a machine learning how to make a decision for itself. Some people say it's like trying to replicate human intelligence through a machine. And though that's true, in some ways that scares me because I don't think we should be replicating human intelligence. I think it's more about gifting technology with enough intelligence to make a safe decision on something.

We are trying to get AI to solve problems for us. And there is a point even in my work, in which you can see that their problem-solving and learning is better than ours. They are better at recognizing patterns than we are, for example. It's better than the human eye.

We're kind of struggling to keep up now because we're trying to develop online dashboards that can handle real-time decision-making updates. It's almost gotten too far ahead of itself because some of the supporting tools haven't actually been developed yet.

One thing about AI, it's only as good as the quality of the data you put in. That's where some people come unstuck. It needs high-quality data to be highly accurate. To put this in perspective, for three months I've been running lizards through the units to fine tune the AI for lizards, geckos and skinks being in there (monitoring stations).

AI is exciting, but do you ever fear it?

Not in the work that I'm doing. Though it does concern me because AI is one of those things that depends on the purpose that you want to develop it for, and then it's fantastic. In some of our work, we've got onboard decision-making — is it a Kiwi or a possum in a trap? This means it's a monitoring device or a track, which can think for itself. It makes a decision by itself. So while it's really carefully controlled by us, you can see that, yes, it definitely has the potential to do things that might be scary.

But it will be game changing for the purposes of conservation.

HOLISTIC TECH APPROACH

Here is a quick overview of just some of the conservation tech projects that Dr Blackie has worked on, and the firms involved in their development.

LONG-LIFE LURES

Called PoaUku, the lure is created using a solid-state, ceramic polymer block that goes through a treatment process to make it highly attractive and long-lasting. A lure that’s as attractive as fresh bait but which will last for months at a time, vastly reducing labour costs associated with replenishing baits. Boffa Miskell Limited and Connovation.

PAWS®

Print Acquisition for Wildlife Surveillance digital animal detection tool. PAWS® technology allows users to detect, identify and monitor wildlife remotely based on their unique body, footprint and weight characteristics which are collected by the unit. The PAWS® units also take photos of interacting species and records the time and date of all interactions. Users can also receive text messages informing them of each animal interaction. Boffa Miskell Limited and Lincoln Agritech.

CRITTERPIC®

CritterPic® is an animal detection system — a long-life image capture device, which automatically takes close-up high-quality pictures of a full range of small to medium-sized invertebrates, lizards, and mammals. Boffa Miskell Limited and Red Fern Solutions.

FLEXI-COMMS

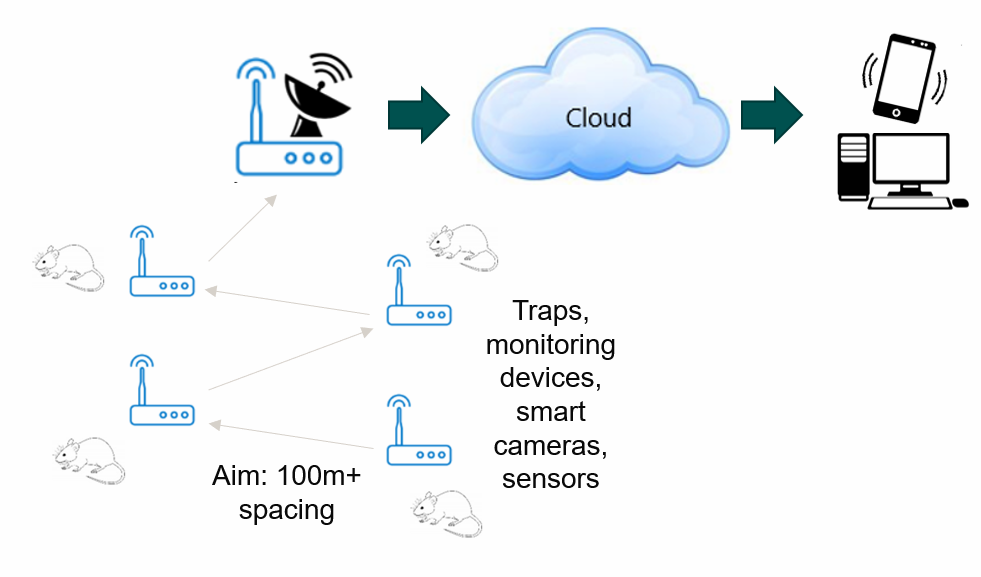

A system to process inputs from traps and monitoring devices, and transmit data to the cloud using Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, cellular, and satellite communications, offering a robust capability to transmit images from remote cameras. Boffa Miskell Limited and Red Fern Solutions.

All the different technologies that you’ve worked with: PAWS, long-life lures, CritterPics, and Flexi-Comms. Ideally, they’re working as an integrated system. Is that sort of the vision?

That's the exact vision. Developing a holistic system has been our goal since day one. I worked on the possum Spitfire, which is a toxin delivery system that is species-specific. That started about 11 years ago, but we realised that if you have something that is out in an environment for a long period of time, you need all these other things to go along with it.

You need something (long-life lures) that continues to attract animals for long periods of time. And then you need a means of communication to know what's going on with that device. And that kind of drove this whole effort: You can't have one thing without the sum of the other parts, or it never reaches its full potential. It's been really challenging from a funding perspective because it's easier to get the small bits funded of the holistic picture. They’ve got their own sort of different funding avenues, rather than one massive project.

Is that funding mostly through the DOC? Or other funding?

It's been a real combo. So yeah, we've got funding from DOC, we've got a lot of funding from Predator Free 2050 Limited. That'd be our biggest project funder. And we have had quite a bit of funding from overseas, particularly from Australia. Some of our tech, we developed the concepts here and then Australia jumped on the bandwagon. When we ran out of funding in New Zealand, they basically funded us for quite a few years to develop tech for them.

But we are in a lucky position now in terms of that sort of integrated solution, we've had almost every project we want to get funded, funded.

In the field of predator control tech, where does New Zealand rank globally?

Definitely a world leader. In some respects, we're a decade ahead. To the point it's almost to other countries’ detriment because there are groups who say "Oh, someone in New Zealand's working on this. So we'll just wait and see how it goes for them. And if it works for them, well, that's great, we'll jump on the bandwagon.”

In terms of collaboration, any other countries that you're working with or hope to work with?

We work with Australia and UK more than anyone else. But I'm constantly approached by people doing island eradications in whatever part of the world that that might be.

The advantage we've got here is that New Zealanders are much more educated about the problem of invasive species. In a lot of other countries, there still isn't the same social acceptance to control them. In New Zealand, we've driven the message home better, and people see it first-hand, that decline of birds and people know that the Kiwi is on its way out. So that's helped us in having society a bit more supportive of the work.

And what about government support, as opposed to what you've seen in other countries? Do you think it's greater here?

At the moment it's greater. Depending on who's in government; it comes in waves. We went through a period where funding almost totally dried up. The biggest change has been driven by the start of the Predator Free 2050 initiative. And that's opened up a lot more funding opportunities, particularly in the tech space. That's been a really big game changer for getting tools over the line. Because there was this sort of drive by the government to fund more blue-sky science or to get proof of concept. So a lot of our projects got there. But then there was no funding to actually help make it commercial. And Predator Free 2050 Limited has filled that gap, saying “If you've got prototype development or proof of concept for a technology which might help, we'll fund you to get it to the commercial stage.” That's always where the gap was.

PESTS LOVE GLOBAL WARMING

How is climate change affecting your field?

Definitely having an effect on the number of predators because, especially the North Island of New Zealand, we aren't getting those cold, cold winters we've had previously, which would naturally knock back some of the predator numbers. Think about that from a population growth perspective, it makes a massive difference. The other effect of climate change is the beech masting events (mass events when beech trees all over the country produce huge amounts of seeds, all falling at the same time). This is our main driver down south of population explosions in rodents and stoats. The warmer weather is causing these events to happen almost annually now where it used to be, say, every five years. So when the seeds are gone, when their food source is gone, predators prey switch and look for another food, usually switching to native birds.

Final question: A predator-free 2050? Are we gonna make it?

Yeah, I strongly think we can. If we have people on board and communities on board, the odds are hugely in our favour. Because at the end of the day, we can have all the amazing technology in the world but unless we've got people willing to go out there and use it, and set it up, and communities to get involved...it won't work.

From a technological and scientific perspective, we can make it happen. When I look at advances in the field over 10 years and think about what might they be like in 30 years, it will be totally game changed again. I think it's doable, so long as we have support from the public.

Story by Cliff Hahn, MOTAT Content Producer

Links:

Boffa Miskell/About Helen

“Generation E: How technological innovations are changing the face of ecology”

Predator Free 2050 Limited: Products to Projects

Department of Conservation: Towards a Predator Free New Zealand

Citation:

Hahn, Cliff. 2021. AI vs. Predator: Will High Tech Tools Lead to a Predator Free Aotearoa by 2050? New Zealand: The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT). First published: 01 December 2021. URL https://www.motat.nz/stories/ai-vs-predator